From Worms to Humans

Imagine looking through a microscope counting the backwards and forwards movements of about 130 tiny worms per week, all while carrying a full-time science course load.

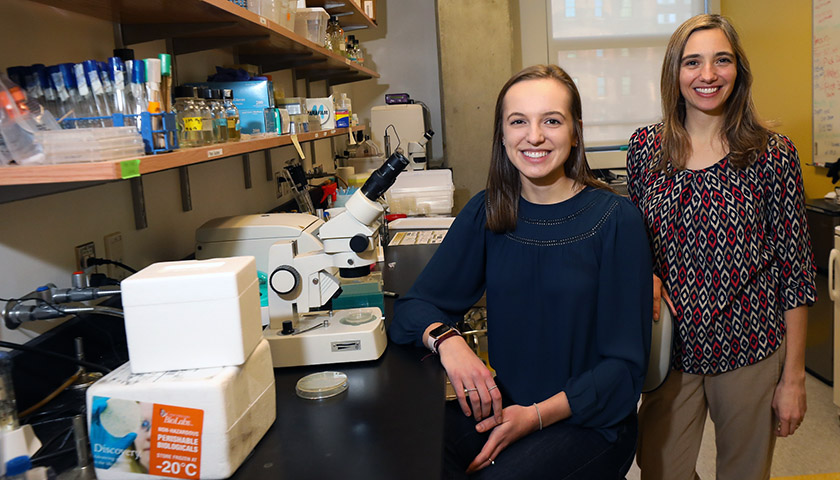

This is how Lily Johnsky occupied her time for two years, beginning as a first-year student.

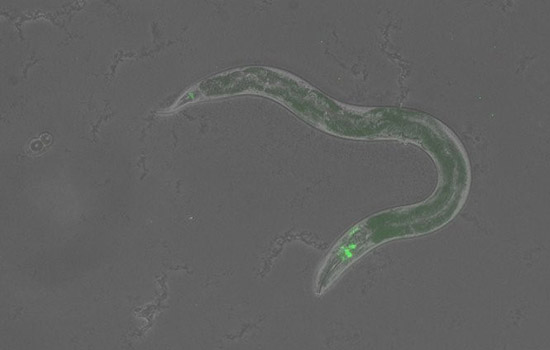

Johnsky, Class of 2019, a biochemistry major and sociology minor, has researched the C. elegans worms in an effort to understand the human nervous system. C. elegans is a model organism for finding out more about how humans send signals throughout their bodies.

“I think it’s cool to take what you’re studying in a dish on a worm and know that’s it somewhat applicable to humans,” said Johnsky, who is now in the process of writing a thesis based on her worked in a lab led by Biology Professor Annette M. McGehee.

Johnsky has studied glutamate receptors, which are a key element in the brain for transmitting impulses in the body. These receptors are found on neurons and are important for both learning and memory in humans and C. elegans, along with many other components involved in these processes.Glutamate, a neurotransmitter that sends signals from one cell to another, binds to these receptors to activate neurons. The activation of particular neurons and neuronal pathways determines the behavioral characteristics of an organism.

Extrapolating to human systems

Since these worms only have 302 neurons, it is relatively simple to map connections between neurons and certain behaviors. In comparison, the human nervous system has trillions of neurons and attachments.

“Studying these tiny organisms gives us a really good indication or good guess of what’s going on in humans.” said Johnsky. “It’s a similar model that you are able to take and manipulate very simply and see a direct response.”

Johnsky studied the protein DMD-10 and found that DMD-10 regulates the glutamate receptor GLR-1.

Johnsky’s findings have laid the groundwork for current student research in McGehee’s lab, and the professor is enthusiastic about her work and skill development.

“It’s been fun to watch Lily from when she was, in her first year, to now putting everything together,” said McGehee. “It’s really nice to see how our students can grow and really become mature scientists writing about things that are pretty high level.”

As she began her research, Johnsky was challenged by the content, because her research, primarily genetics-based, sprang ahead of what she was learning in her science courses. But her determination allowed her to develop independence in the laboratory.

“It really forced me to learn things really well on my own and then directly apply them to what was going on in the lab and research.” said Johnksy. “I approach questions in class differently because I know how to think things through really clearly and efficiently, and I am able to predict results with a better guess.”

Atmosphere of encouragement

Johnsky values McGehee’s support and the way that Suffolk’s supportive environment has allowed her to grow as scientist.

“I like that there is no boundary between Dr. McGehee and me. I’m not working in between some graduate student or postdoc, like you would at larger schools.” said Johnsky. “Working at a smaller school like Suffolk...you gain so much more experience and control of your own project.”

In addition to being a busy research assistant, Johnsky makes time for campus involvement. She is president of the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology (ASBMB), meets prospective students and families to help them learn about Suffolk, and has volunteered for Suffolk’s Alternative Spring Break program with Habitat for Humanity.

“A lot of this research is your own time. You’re fitting it in among all your other work, and it’s not just work you’re doing in the lab,” said Johnsky, “You’re reading papers after the lab, you’re typing up protocols and notes, and I think it really gives you a sense of independence and responsibility.”

'A go-getter'

McGehee recognized Johnsky’s dedication to her research right from the start.

“Lily’s a very hard-working student. One of the reasons she started with me as a freshman was because she was a go-getter from the beginning,” said McGehee.

Johnsky's skill set and abiding responsibility made her a “very good asset” for the lab, and she was the first student McGehee entrusted to train incoming student researchers.

Presenting research

In 2016, Johnsky won a poster competition at the regional Eastern New England Biological Conference, or ENEBC and went on to present her research at the national ASBMB Experimental Biology conference in San Diego.

When she leaves the worms behind after graduation, Johnsky plans to apply to medical school, with the aim of becoming an emergency medicine and pediatrics physician. She believes that her research with worms led her to recognize a drive for working with people and pursuing clinical research.

“I definitely went into school thinking that I wanted to pursue a research career, get a PhD, and work in a lab,” she said. “I’ve always been interested in clinical research and health. This research showed me that I love working in a lab; I love problem solving, but I found that there was a component missing. I’ve always known that I want to interact with patients and follow patients throughout a course of treatment, but don’t think I want to actually be conducting the research. I want to be on the other half.”

Contact

Greg Gatlin

Office of Public Affairs

617-573-8428