Behind the Badge

In a year of sharp divisions, few felt harder to heal than the gulf that opened up between law enforcement and communities of color following the killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor.

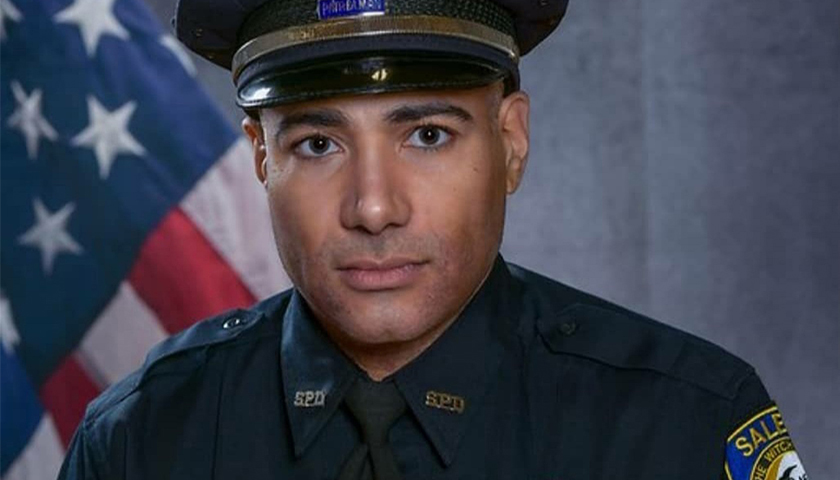

Every morning, Neil Sicard, BA’00, wakes up with a foot on each side of that gulf.

Sicard is Black, and he’s known from an early age how it feels to be racially profiled. Yet he’s also a cop, a proud member of the Salem (Mass.) Police Department since 2017. He spent part of the past summer patrolling the city’s Black Lives Matter rallies, where some protesters jeered at him, calling him a sellout.

Near the end of the summer, his cousin called him to check in. “He told me, ‘What a year to be a cop. Nobody likes you,’” Sicard says with a rueful laugh.

The thing is, Neil Sicard loves being a cop. He’s wanted to be one ever since his junior year at Suffolk, when he had an internship with the juvenile probation office at the Moakley District Courthouse.

A sociology major, he’d entered college with thoughts of becoming a lawyer, but it was the police officers who caught his attention, “because they knew more about the kids coming through the court system than anyone else”—their backgrounds, their family histories, and what they needed to get back on track.

The son of Haitian immigrants, Sicard grew up in Revere, a close-knit, still largely Italian-American community “where if you respected your elders, you were treated like family,” he recalls. His next-door neighbor was a firefighter who introduced him to local cops, and Sicard loved listening to them talk shop.

But the older he got, the more race and ethnicity seemed to matter. Teachers, who’d once seen him as a diligent student, now seemed to regard him a troublemaker. After he pointed out a quicker way to solve an equation, one high school teacher told him he was being belligerent and sent him to the principal’s office.

Sicard came to Suffolk in search of community. He found it, first as a member of the University’s Caribbean-American Student Alliance, and then as a student in Professor Robert Bellinger’s newly launched Black Studies Program.

He grows emotional recalling what it was like to sit in a classroom surrounded by other Black students, studying the full history of the African diaspora and the range of African-American achievement. “Professor Bellinger brought back our confidence,” he says. “He gave us knowledge we had been robbed of when we were younger, and showed us how diverse we are in our history and culture.”

Patrolling while Black

After graduating from Suffolk, Sicard earned a master’s degree in criminal justice from Northeastern, and took a job as a Boston Special Police Officer. Patrolling health clinics and housing developments in the South End, he learned the fundamentals of community policing. He later moved to Salem to work as a security supervisor at the Peabody Essex Museum and at National Grid, but never lost his interest in law enforcement. After passing the civil service exam, he applied to the Salem Police Department.

With no family connections or friends on the force to pull strings, Sicard started as a reserve officer and worked his way up. “I took the long road,” he says. After graduating from police academy, he was sworn in as a patrolman in April 2019, one of the proudest moments of his life.

One year later, he was dealing with crises that no amount of training could have truly prepared him for: the outbreak of COVID-19, followed by the murder of George Floyd and the racial justice protests that swept the country.

The protests in Salem took a toll on Sicard, who found himself caught between demonstrators whose basic goals he understands and a police department he feels “blessed to be part of.” As a Black officer, he found it ironic, even humiliating, to have white protesters yelling “Black lives matter” in his face.

“I thought, ‘Are you serious? When the protest is over, you can melt back in your world. But as a Black man, I can never do that.”

He agrees with a friend on the Boston police force who says that Black cops can feel like they are under more pressure than their white peers—namely, the pressure to always be perfect and never really speak their minds. Criticism from within the Black community also stings. “Our ancestors fought so we could be in these kinds of positions of power,” he says. He worries that fewer people of color will want to work in law enforcement.

Finding the middle ground

While the protests have subsided, Sicard still finds himself straddling that gulf between Black and Blue Lives Matter, “watching extremes on both sides yelling past each other and not working for resolution.”

No one has to explain systemic racism to him, nor the fact that there are bad cops. What he doesn’t support is the notion that racism begins and ends with law enforcement.

“When you see officers who have done bad things or acted on their biases, step back and ask where they came from,” he says. “They came out of your communities.”

The responsibility for addressing that racism belongs to everyone, he says—including wealthy white communities whose residents post BLM messages on social media, but don’t grapple with their own history of discrimination. (Says Sicard: “As kids, we all knew we couldn’t go to Marblehead because people would call the cops.”) If people truly care about Black lives, he says, “actions will speak much louder than words. Start encouraging more Black people to live and work in your community.”

Sicard believes police officers face an extra level of scrutiny because their work is public in a way that many jobs are not—for example, bankers who deny loans to minority families, or store owners who follow Black teenagers while they shop. What gets lost, he adds, is that policing “is a very human job. These are human beings doing stressful jobs in stressful situations, and they can make mistakes.”

He saw that up close last June when a Salem police captain posted an angry tweet on the department’s official Twitter account, criticizing Boston Mayor Marty Walsh for allowing large BLM protests while limiting the reopening of restaurants. Although she quickly deleted the tweet and reported it to the chief of police, demonstrators rallied outside the police station, calling for her to be fired.

Sicard was no fan of that tweet, but he knew something the demonstrators didn’t: the police captain had hired him, and she had made a point of checking in with him regularly. “I wanted to tell people, ‘Time out, she’s not a racist,’” he says. “But passions got so heated, the chance to actually communicate was lost.”

In the final days of 2020, the Massachusetts State Legislature passed a major police reform bill. While the bill has been widely praised by civil rights groups, Sicard says he’s concerned that it was rushed and politically motivated, and may not lead to lasting reform. Real change, he says, also requires education. Schools need to teach Black history in all its fullness, he says, and show how this community helped build the country. Police academies, which already have courses on bias and hate crimes, need classes on the history of tensions between Blacks and law enforcement. And the general public needs to learn more about the men and women behind the badge.

“There’s an echo chamber on both sides, and we need to find the middle ground,” Sicard says. “That’s something that my Black Studies courses taught me. We have to know our history and the underlying stories to understand how we’ve reached this breaking point.”